The Future of Journalism: Media Bias, Misinformation, and the Search for Truth

Interview By Brandi Fleck

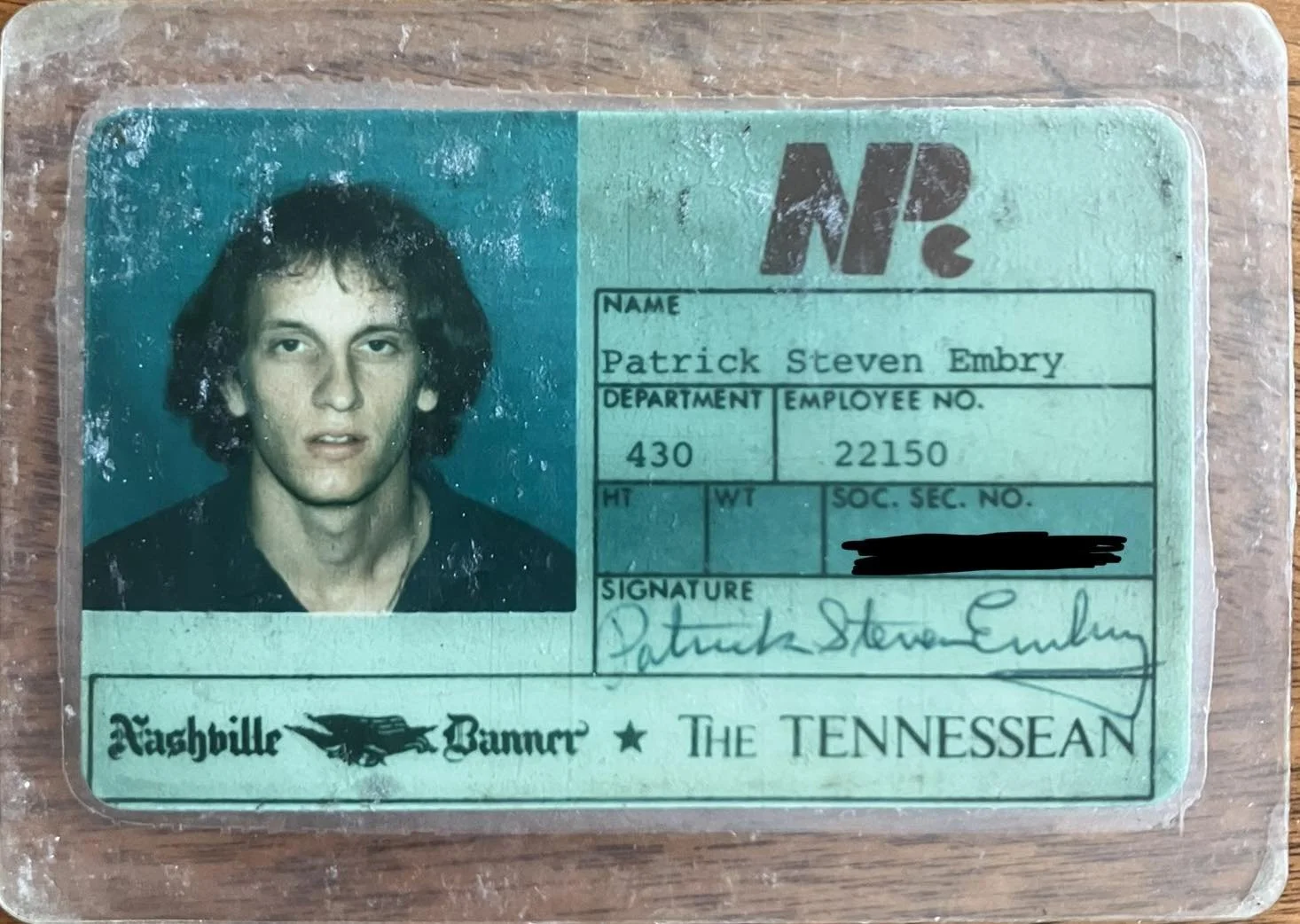

Pat talking to a colleague at the Nashville newspaper, The Tennessean. Photo provided by Pat Embry.

This is a candid and compelling look at the evolution of journalism, the rise of propaganda, and why protecting truth in media is essential to democracy with veteran Nashville journalist Pat Embry.

In this episode of Human Amplified, we welcome Pat Embry, a longtime Nashville journalist who has held roles as an editor at the Nashville Banner and The Tennessean, director of the John Siegenthaler Chair of Excellence in First Amendment Studies at MTSU, and communications director for the Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee.

With nearly 50 years in journalism, Pat has witnessed the industry evolve from print to digital, seen media ownership impact editorial stances, and observed the growing difficulty in distinguishing truth from propaganda.

Pat reflects on his career and emphasizes the significance of responsible reporting and critical thinking in navigating today’s polarized media. Our conversation underscores the vital importance of a free press in shaping informed citizens and a resilient democracy.

Listen to Pat Embry’s Interview

We Talk About

02:16 – What does being human mean to Pat Embry?

03:00 – Pat’s journalism background and career journey

04:35 – The transformation of journalism over the years

12:15 – The current state of journalism and the role of journalists as first responders

17:25 – How to determine the truth when media outlets report different narratives

22:05 – What is propaganda, and how does it influence the media today?

28:25 – How multiple sources help verify accuracy (but why it’s more complicated than it seems)

30:55 – The difference between subjective and objective journalism

34:25 – The Associated Press: Why it remains a trusted source

38:10 – Why journalists are vital to democracy

40:00 – Pat’s thoughts on the future of journalism

Watch Pat Embry’s Interview

Read the Transcript with Pat Embry and Brandi Fleck

What Does It Mean to Be Human?

Brandi:

What does being human mean to you?

Pat:

I believe humanity involves being thoughtful as opposed to being thoughtless and being aware as opposed to being unaware. And I think our ultimate goal is to, like journalism, oddly—I picked that field back when I was 10 years old—was you engage, enlighten, and illuminate. So does that answer any of it?

Brandi:

You did. Thoughtful and aware, which I think is a really interesting perspective on it. So thank you, Pat.

Pat:

You're welcome, Brandi.

Introducing Pat Embry: A Veteran Nashville Journalist

Brandi:

Everybody, today we are welcoming to the show Pat Embry. He is a longtime Nashville journalist who's now retired, but Pat, you were an editor at the Nashville Banner, the Tennessean, and of the best-selling guidebook based out of Brentwood, Tennessee called Locals Eat. Then you became the director of the John Siegenthaler Chair of Excellence in First Amendment Studies at Middle Tennessee State University. And your latest position, which you retired from, was the communications director of the Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee.

And so this rich experience and firsthand involvement with media and its evolution is why you are such an amazing guest to talk to about what we're going to talk about today, which is the current state of journalism and how we can all have discernment when it comes to misinformation and propaganda and what's even real anymore. So welcome to the show and thanks for being here.

Pat:

Thanks for having me, Brandi. Yes, as all the interns I've worked with, you're my absolute favorite and don't let anybody tell you otherwise.

Brandi:

I bet you say that to all the interns.

Pat:

But how could you really know?

Brandi:

I know. I actually told my husband the other day, I was like, I am so excited that I get to talk to Pat Embry because I feel like I was very fortunate to have had you as a mentor early in my career. And seriously, it's been amazing. So thank you.

Pat:

It's so sweet, and going on 50 years that I've been in the business. The Banner folded after 122 years, and Locals Eat folded, and on and on. But I did leave MTSU for the Community Foundation.

Journalism in Transition: From Print to Digital

Brandi:

You know, you mentioned that these things folded, but I think that in the height of your career, journalism was shifting and changing all throughout it. Print was sort of dying. Digital was coming about. So much changed as you were in the throes of it.

Pat:

Yeah, I was told when I went to journalism school in the mid-70s—that's how old I am—“Oh, you don't want to go into journalism because the journalism programs are packed to the gills.” This was right after Watergate. Everybody had visions that we all looked like Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman. And, you know, people would meet you at a parking lot and tell you all these secrets.

And I told people at the time, well, it's too late because that's all I've ever wanted to do since I was 10 years old. And I certainly knew enough from growing up in a small farming community that I didn't want to work at a farm. I had factory jobs. My first job was a paper route when I was 10 years old and I ended up having three. That's just a small town, so it's only a mile wide. It's not like I was old enough to have a car.

And back then you didn't throw the paper unless the dog was chasing you. If Mrs. Jones wanted the paper in her living room, that's where you put it. You just opened up the screen door and boom, there it goes. So it was all individual.

But I've been reading papers—multiple papers—every day since I was about five or six years old. And then when I was working in the business, folks told me at the time, Brandi, “You know, journalism's dying. People aren't getting their news that way. They're going to get it from television.” And then the same thing happened when the internet and online came about. It's just different now. There's still print.

I've told folks for at least 40 years, I don't care if they're beaming that content off my eyelids. It doesn't matter to me. I haven't had a print newspaper delivered to the door in going on 10 years.

Much to my wife's pleasure, because I still read so many newspapers. If they were still with newsprint, you could tell the places I lived because there was newsprint on every drawer. Kitchens that are lighter—well, not my house, because every place has newsprint everywhere. It's on your face. I mean, it's just ridiculous, but that's how much I care about the format.

But yeah, now I have no problem at all. I prefer reading magazines on an iPad. And I still prefer reading actual books instead of using a Kindle or something. I just like the feel of it. But otherwise, I'm not bemoaning what's left of newspapers.

The deadline for the Tennessean now is 2:30 in the afternoon for the next day, which means they have no news that's even remotely close to being breaking. It's just different. And back when I was at the Banner as an afternoon newspaper, something could happen at quarter to noon, and it would be in the afternoon paper.

Covering Breaking News in the Pre-Digital Era

Pat:

A lot of the court stuff, a lot of the political stuff coming from the state capitol all happened in the morning. And then an inordinate amount of mayhem—the Challenger exploding, the whole Gulf War in the early 90s—was all really done on our time.

And this sounds kind of grisly, but since I'm balancing my phone right now, it's cradled on The New York Times Book of the Dead, which is spectacular. It's the size of dictionaries back in the day. And I love obituaries anyway. I think that's sometimes the first and the last time people are memorialized.

I can still remember the celebrities that died on Banner time, which is good and really kind of macabre. Roy Acuff, for instance, who is one of the fathers of the Grand Ole Opry. The Banner was a traditional Republican newspaper, but it sure wasn't by the time I ended up going down with the ship, because you couldn't tell our editorial stances from the Tennessean’s to save your life.

Anyway, I'm working the city desk at 4:30 in the morning, and I get a call from Baptist Hospital from a friend of mine named Eileen Katcher. She goes, “Pat, I have bad news that Mr. Acuff has passed.” He'd been sick for quite some time.

So I hang up with Eileen and then call my music writer, who I'd specifically sent to the Opry that weekend and told him to interview anybody he could wrangle to talk about Roy because he was on death's door. So I brought him in. He hadn't even broken down his tape and quotes yet, but he worked on deadline. Our obituary writer had worked on the obit for at least 20 years, updating it, fluffing the pillow, and all that.

So we get it out. He's leading the paper, obviously. And then between editions, Roy Acuff was buried. So we got to change, we got to update it. We won second place in the Tennessee Press Association for breaking news—for an obituary that was started 20 years ago. I mean, that's pretty incredible.

So now I bemoan people who died on Tennessean time. Like, why? Why did you do that? You could have been with us, right? Isn't that awful?

Brandi:

You bring up a really good point with the fact that there just isn't breaking news in newspapers anymore. And that brings me to the question: What is the current state of journalism, in your opinion?

Journalism Under Fire and Its Role in Democracy

Pat:

It's cautious. It's always been that way. I think having the president of the United States, off and on over the last several years—and this dates back to eons as well—saying that we're the enemy of the people… there's a reason why journalism is the only profession that's mentioned in the Bill of Rights. It's because we've always been the folks who keep government honest. And that's still the case.

You can pick any time through history. Now is a lot squirrellier than what it has been in the past, but I grew up in the Richard Nixon era. I know what comes out of it. And this will touch some on propaganda and what's real or not. What comes out of an elected official's mouth—whether it's your city councilperson or the president of the United States—what comes out of their mouth is not necessarily what’s happening. You have to rely on quality news sources. By “quality,” I mean folks who get the closest they can to the truth—what really happened, the nuances, all of that. To this day, I believe newspapers are where that's still coming from.

Local Journalism as First Responders

Pat:

I don't care where they're published. The Nashville Banner has been revived as an online product. It's been out in full throttle for over a year. It's a free publication now, but I pay them money because it's the right thing to do. They're trying their best. They work really hard. They're trained journalists. And they're at their best when horrible things happen—whether it's weather or a school shooting at Covenant.

For instance, a couple of years ago, the education reporter was coming back from another assignment around Rutherford County. She hears the dispatch, points her car in the direction of Covenant in Green Hills, and off she goes. It's like first responders. Journalists are first responders, and that's the case now, just like it was when I broke into the journalism world. That hasn’t changed, nor will it.

You want to have somebody who knows how to get the information, what questions to ask, how to be sensitive about it, and still get the story out. And maybe not surprisingly, the next day those papers sell out.

Why Print Still Matters: Iconic Images and Lasting Impact

Pat:

You don't really know something has existed until you can see it in print, which is odd if you think about it. But think about wars, conflicts, and major events—what do you remember the most about them? Most of the time, it's a still photo, even though everything is on video now.

In the Tennessean’s case with the Covenant shooting, the photographer, a young journalist named Nicole Hester, had the shot. Boom, boom, boom—everything happened so fast. You can still pull up the security camera footage from inside the school, but the image that endures is the one she captured. It was a little girl with tears in her eyes, her face pressed against the glass of the bus as they evacuated children to the church down the street in Green Hills.

Brandi:

I remember that photo.

Pat:

Yeah, well, that's the example. There wasn’t anything else to shoot down there anyway. And the kids are ultimately, as so often is the case, the window of society for us.

Just like if you want to find skullduggery in government, you follow the money. That remains true to this day. Name your level of government, and chances are if you follow the money—you’ll find it. Won’t mention any names… Elon Musk, you know.

History Repeats Itself

Pat:

If you go back to what being human is about, it's also about: what does history show us? Stay up on your history. If we just did that, there’s nothing happening in Ukraine that hasn’t happened time after time through history.

We’ve seen the likes of Donald Trump before—demagogues, autocrats. Think about the Gilded Age, when an inordinate amount of people had most of the money. We've been here before. So if you keep to that, then you know not to be surprised. One, and two, let’s take care of each other. If we can do that, then we’ll be okay.

But I believe journalism is still front and center. It separates us from total mayhem. It’s easy to downplay, though. I worked at the Banner 18 years, and 16 of those 18 years we lost circulation because it was an afternoon paper. I was asked every single day, “When's the Banner going to fold?” Every single day for 18 years in some way, shape, or form.

Getting Closest to the Truth

Brandi:

Pat, one thing that really stood out to me when you were talking is you described journalists as people who get the closest they can to the truth. And that's what is hard for me personally right now, and I think other people struggle with it too.

I’ll give an example—the Super Bowl. There’s a lot of stuff going around right now. And this episode is going to come out in March, so for listeners, we’re recording this in February, a couple of weeks after the Super Bowl. There are stories going around about how President Trump was booed, but Fox chose to edit that out or not cover it. And then there are people saying, “Well, the rest of the world saw it. You're not fooling us. Why are you trying to present it in a different way?”

It’s really difficult to tell what actually happened if you weren’t there. So what would you say someone should do to even know what the truth is—or who got closest to it?

Media Bias and Propaganda in News Coverage

Pat:

Well, you mentioned the network, right?

Brandi:

There are people.

Pat:

The only time I watch Fox, just to be brutally honest, is for a sporting event. Maybe I’m jumping the gun on propaganda, but there’s no question that the commentators—and they’re not reporters—every night on Fox are spreading propaganda for the Republican Party and in particular for the president. They don’t make any bones about that.

That’s how Rupert Murdoch set it up, and Roger Ailes as his devil in charge back in the day. It was totally set up that way. And contrary to popular belief that “the media” is one thing—which I hate, by the way—there’s never been a national TV station like Fox set up like that.

The progressive or liberal side, the so-called “blue states”—MSNBC has never been more than a wisp of what Fox is. So, of course, Fox isn’t going to show the president being booed. Some stuff makes good TV, some stuff doesn’t.

I don’t think that’s a calamity. One of the hardest things for me—and this goes back to journalism, Brandi—is that folks say, “Well, I don’t want to pay for my media.” And you go, “Well, do you know, have you followed media through the…”

Why Paying for News Matters

Pat:

Follow television through the history of television—or follow newspapers or magazines—what do they all have in common? They have advertising.

In the 50s through the 70s, it was Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom, right? A popular show on Sunday nights, brought to you by Mutual of Omaha, an insurance company. Or the Texaco Hour starring Milton Berle in the 50s—the biggest show on television—but it was brought to you by a sponsor.

The Banner was, I don’t know, let’s say 35 cents when I worked there. You can’t get a stale donut for 35 cents now. People griped about the money even then, but it was filled with ads.

Brandi, I presume you never took a course specifically in how to research?

Brandi:

Not specifically, yeah.

Pat:

They just expect you to learn. But I think it should be required—certainly by high school, if not middle school—to teach students how to research something. And that’s the same thing we’re talking about: is it a trustworthy source? Why is it trustworthy? You need multiple sources. It’s the old saying: if your mom tells you she loves you, get a second source. Does she really love you, or does she love your sister more? You just don’t know.

Political Lies, Propaganda, and Media Literacy

Pat:

You see this every day, and after a while—particularly with politicians, name them, it doesn’t matter—they are prone to exaggeration and complete falsehood.

No, Ukrainians did not start this war with Russia. Russia did. Everybody should know that by now. But guess what the president of the United States said in the last 18 hours? “Russia didn’t start it.” Come on. That’s just not true. No small country suddenly decides, “Yeah, let’s go back under a massive authoritarian regime we worked generations to escape.” Why would we buy that just because the president says it?

Brandi:

That’s a really good question.

Pat:

Yeah. But why do you watch Fox News?

Brandi:

Well, when we were talking about Fox News, you mentioned how it’s structured. And I think a lot of people don’t understand how certain outlets are structured and why that makes them less “news” and more entertainment. I also think knowing how an organization or outlet is structured can help you determine if it’s propaganda or not. So what are your thoughts on what propaganda is—and what it isn’t?

What Is Propaganda?

Pat:

Thanks for the question, Brandi. The word “propaganda” is loaded. What’s propaganda, what’s not—and can you tell the difference?

Propaganda’s first cousin is advertising and marketing. Do you want to use Bounty as your paper towel of choice or not? If you watch their ads, you might say, “That must be a spectacular product. They spend so much money.” But that doesn’t mean it’s the best paper towel. That’s propaganda, by definition.

Propaganda is normally used in politics, but it applies to products too. You may not like Bounty because the sheets are too big, and you prefer smaller ones. You’ve got to break it down like that.

You have to do the same thing with media. If the ownership is weighted one way or another, it colors the coverage. My feelings on the Washington Post are different than they were several months ago because Jeff Bezos—the gazillionaire who started Amazon—decided the newsroom wouldn’t endorse Kamala Harris or anyone else. That’s his prerogative as owner.

Who Owns the News?

Pat:

Look at the history of news in this country. If you know anything about the Confederacy, Jim Crow, all of that—we need to continually study it. One of the few national newspapers that cared enough to cover civil rights back then was the New York Post. Odd, since now the Post is owned by Rupert Murdoch, and that’s not what they do. Today, it’s sensational and politically weighted.

So ownership matters. You’ve got to know who owns a publication and where they stand. If I were your professor and you turned in something sourced from Breitbart, I’d ask, “That’s your source?” Because Breitbart is a right-wing propaganda publication. They don’t make any bones about that. But if you just Google something and it pops up, you might think, “Oh, that’s a legitimate news source.” Well, it’s not.

Where it gets even muddier: sometimes you’ll see a Forbes byline. Forbes is respected, even though its owner leans conservative. But they also sell the right to publish. You and I could pay to have a story run under Forbes’ banner. It carries the Forbes name, but that doesn’t mean it’s legitimate reporting.

You can’t do that with The New York Times. They have a bank of editors vetting information, filtering out the falsehoods. That’s why it’s mystifying when false claims slip through. But one of the reasons we need journalism is to keep people honest.

At the end of the day, believe what you believe—not because somebody told you on Fox, or you saw it in a meme, or you tuned out entirely. Saying “I don’t keep up with the news, it’s just so horrible” doesn’t make the world less horrible.

Good News in Media

Pat:

Having worked for newspapers for nearly a quarter century, I can say there’s so much good news in media. You just choose not to read it—or not to remember it.

Every obituary is a story about someone who lived an ordinary but meaningful life. You learn about moms, dads, grandparents—people who shaped their communities quietly. It’s important we herald that.

But turn on any local TV station and you’ll see endless mayhem—because there are pictures and video. It feels like there’s chaos in the streets every night. That’s not reality. It’s “if it bleeds, it leads.”

Meanwhile, real-life successes, like a second-grade class in Bon Aqua learning to read, don’t make the broadcast. Watching kids learn isn’t sensational enough for folks who get all their news from local TV.

I say this as a print guy, obviously. But I’ll add this caveat: I also wouldn’t ever want to miss CBS Sunday Morning, because I think it’s the best news show on television.

Guarding Against Misinformation

Brandi:

Okay, before we wrap up, Pat, I’d like to summarize what I think you’ve presented as ways we can guard ourselves against misinformation, biased information, or propaganda.

I’ve heard you say sources are important. You want to follow publications or outlets that usually get their information from more than one source. Actually, wait—I’m backtracking. I was going to say you can know the information is true if you see it reported in more than one source, but maybe that’s not quite right.

Pat:

Yeah, it’s more complicated than that. I guess it’s: who do you believe?

I won’t use any names here, but you know who we’re talking about. If someone is a chronic liar—chooses not to be factually accurate, grossly exaggerates, or twists things—chances are they’ll do that continually.

There are publications, like The Washington Post, that do a great job of fact-checking. They even have one reporter whose entire job is fact-checking lies. If you’re caught lying, you get Pinocchios—four Pinocchios for a total falsehood. So, you’ve got to trust sources—not just journalism sources, but also the individuals speaking.

For example, Dr. Schaffner at Vanderbilt is an expert on infectious diseases. He’s quoted everywhere. What he says is most likely accurate because it’s his field, his career, his expertise. You can check his research against others, but chances are, if Schaffner says it’s true, it’s true.

That doesn’t mean there aren’t variations. For example, maybe 2% of people who took the COVID vaccine had bad reactions. But that means 98% didn’t. Does that mean you throw out the vaccine because of the 2%? Common sense says no.

It comes back to being aware and thoughtful—the basics of humanity in a civilized society.

Knowing Who Owns the Media

Brandi:

Okay, so we covered the source part of finding the truth. The other two things that stood out while you were talking were:

Know who owns the outlet and what their background is, so you know whether they’re pushing an agenda or have a more objective editorial stance.

A publication is more credible if the writers are reviewed by an editorial team and aren’t just paid contributors.

Is that correct?

Pat:

I would caution—there’s nothing in journalism that is fully objective. It’s all subjective.

For instance, if you’re shooting a documentary with one camera, the story depends on where that camera is placed. It can only show part of the story. So, by definition, it’s subjective.

What you and I believe—or don’t believe—doesn’t make it true. We all bring our biases to the table. Journalism is about trying to get as close to the truth as possible.

Was January 6th a friendly gathering with a few knuckleheads, or was it orchestrated? Was the 2020 election stolen or legitimate? We know what happened. We watched it. It’s been battled in the courts for years, and 2020 was a legitimate election.

But not a single person newly in the cabinet will admit it. Why? We don’t know. To me, it’s clear: we have government officials who are lawless. And many people seem okay with that. Some even think it’d be fine to have an autocracy for a while—something closer to royalty, where laws are based on whatever leaders want.

That’s not how democracy works. Germany was a democratic country in 1932. By 1933–34, it wasn’t. It took just a few twists of the dial. It’s always framed as “law and order,” or “why worry about the world when we can’t worry about ourselves?” And then you start demonizing people who look different, worship differently, or have different skin color. This has happened throughout human history—and it’s happening right now.

The thoughtful person knows the difference. You’ve got to trust your senses. If something feels wrong, it probably is. Pay attention. Think.

The Importance of Watchdog Journalism

Pat:

Money can whitewash a lot of things. But we owe it to ourselves not to bury our heads in the sand. Don’t say, “This disturbs me too much, I’ll just ignore it.” That’s not what we’re supposed to do as citizens.

People badmouth their local publications all the time—it’s practically a sport. But if you want to know the news, you need to get it from legitimate operations. Watchdogs who cover government. That’s part of journalism’s founding purpose.

And the Associated Press—AP—is the ultimate in non-biased reporting, no matter what people say.

Brandi:

I was wondering if they still were.

Pat:

Oh, God, yeah. Absolutely. They’re squeaky clean. AP is the bedrock of American journalism. They may have fewer people now, because fewer outlets want to pay for AP, but they remain absolutely essential.

There’s a reason AP isn’t welcome in certain spaces now. Their Stylebook shows how to best label transgender people in the most humanistic way possible. The current regime—yes, I call it a regime—doesn’t agree with that. They want it wiped out, like they want to wipe out history. They want the rules to be only their rules.

Brandi:

They want to control the narrative.

Pat:

Exactly. They want to control the narrative and everything about it. And they want to punish their enemies unless you conform. That’s what bullies do. That’s what autocrats and dictators do.

It’s a takeover. It’s a hard time, and also a great time, to be a citizen right now. We’ve got so many great things happening, but at the same time, too many of us keep our heads in the sand.

Defining Truth in Journalism

Brandi:

One closing thought I’d love to end with is this: when I was coming up in journalism school, we used to talk about how journalists are the writers of history. We are the first line of recording history. And if the standards go down—or if the narrative is controlled by someone with an agenda—then the record of history isn’t accurate.

I didn’t plan to ask you this, but how do you define truth?

Pat:

How do you define truth? Truth is always in the eye of the beholder, for starters. There’s no such thing as “the” truth. There is such a thing as what’s actually happening, why it’s happening, and how we can promote or disallow it in our society.

Sometimes it’s an easy answer, sometimes it’s a harder one. But you have to have people in charge who actually do the work. You have to have experts doing their jobs. You can’t throw away the checks and balances, as much as politicians want to.

They don’t want journalism schools, for starters. They don’t want anyone practicing journalism because they don’t want anyone checking on them—unless journalists are cowed into following the party line.

It’s like what you learn as a parent: “No, you can’t have a cookie before dinner.” Why? Because it will spoil your dinner, and if all you eat is cookies, that’s not healthy. You can explain that, but if you leave it up to just anybody, they’ll say, “I’m going to eat a cookie.”

Well, don’t let people just eat cookies. Don’t let yourself consume only the sweet stuff. There’s always bias, but balance matters.

Why Journalism Is Essential to Democracy

Pat:

Journalism is the most important profession. It always has been in a democracy. You have to have it. That’s the first thing dictators do: they get rid of the journalists. They don’t want anybody watching. That’s what’s happening with AP right now.

Brandi:

Yeah. They get rid of the real ones and then call the propaganda machine “journalism.”

Pat:

Absolutely. But there’s no journalism in that. Sticking a mic in your face while you blather about whatever—that’s not fact-checking. Most people don’t even care if it’s fact or fiction.

Hard work never hurt anybody, and doing the right thing never hurt anybody. Treat people how you’d like to be treated. And I believe most journalists I’ve worked with over the years believe in that. That’s why they’re journalists. There are easier ways to make a living. Working on deadline is not for everyone.

But I’m thankful I’ve been able to thrive. I’m thankful that you, Brandi, are another intern I can look back on fondly. My advice to you—and to any journalist—is that it could be so much worse.

Brandi:

Absolutely.

Pat:

I hope I’ve been a good influence on generations of journalists.

Brandi:

I know you have.

Pat:

In this area, it’s not hard to check up on me. I’ve probably worked with most people. I love the profession and obviously can’t live without it.

Closing Reflections

Brandi:

Thank you, Pat, for your insight today and for your contribution to journalism in Nashville. I feel very grateful to have been able to talk to you.

Pat:

Oh, thank you. I appreciate the kind words. It warms my heart that folks I’ve worked with—most of them younger than me at this stage—have gone on to succeed, raise families, and make a difference every day. I don’t take that for granted, and I deeply appreciate it.

Links and Resources

Join the conversation!

Feel free to share your own experience and let me know if you have any questions in the comments.

Related Posts

Hi, I’m the founder of Human Amplified. I’m Brandi Fleck, a recognized communications and interviewing expert, a writer, an artist, and a private practice, certified trauma-informed life coach and Reiki healer. No matter how you interact with me, I help you tell and change your story so you can feel more like yourself. So welcome!

Find More on the Blog

Topic

- Black and BIPOC

- FAQ

- LGBTQIA plus

- Nashville

- UFOS/UAPs/ETs

- abuse

- accountability

- addiction and recovery

- affirmations

- afterlife

- angels

- animals

- anxiety management

- art

- astrology

- awakening

- behind the scenes

- being human

- body image

- body work

- boundaries

- brandi fleck

- breathwork

- burn out

- cancer

- career

- chakras

- channeled

- clarity-dive

- clarity-practice

- clarity-primer

- coach

- communication

- community

- confidence

- conflict resolution

- connection-practice

- connection-primer

- consciousness

- creator

- crystals

- dance

- dating

- death

- decision making

- disease

- divorce

- education

- emotional health

- energy work

Recent Blog Posts

Visit the Full Podcast Audio Archive

Affiliate